Google UX director teaches the best way to map out critical user journeys

Shane Schick tells stories that help people innovate, and to…

It could be nothing more than a tech industry myth, but the way Dr. Javier Bargas-Avila tells it, an incident involving one of Google’s co-founders offers an object lesson in why designing the right experiences is so important.

During his keynote speech during Alida’s virtual Innovation Day earlier this week, Barga-Avila – who serves as the search giant’s UX director – recounted how Larry Page was reportedly asked by a friend to help set up his Android phone. The Google co-founder said yes, but soon found himself growing upset and frustrated by having to create multiple accounts and link disparate applications.

“There were good flows and good products, but they didn’t really work together,” Barga-Avila said. “And that was because nobody had actually looked at the user journey that somebody takes when they set up the phone for the first time, and nobody was in charge of that.”

This speaks to an issue Barga-Avila raised in his keynote: the fact that many product teams, and even entire organizations, are less user-centric than they claim to be. And while user experience (UX) design may be one facet of a brand’s overall customer experience (CX), the shift to digital channels for an increasing range of activities means it plays a vital role in overall customer satisfaction and loyalty.

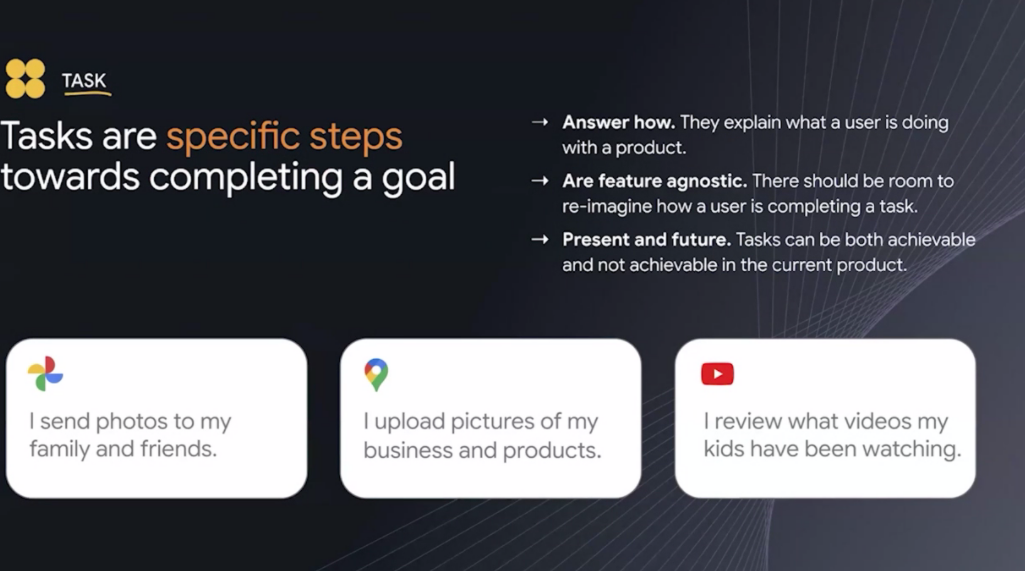

Google’s approach has been to focus on what Barga-Avila called “critical user journeys” (CUJs), which combine a user’s goals with the set of tasks they need to complete them. He gave the example of a consumer who wants to share memories with family and friends using images stored in Google Photos, or a small business that wants to ensure its customers can find its contact details using Google Maps.

The tasks users take to achieve those goals may involve your company’s products and features, Barga-Avila said, but also those of other organizations. Some tasks will happen outside the use of a digital application or tool. Good UX also takes into account how these tasks might be completed now as well as in the future, he said, and identify tasks that aren’t achievable within the current product.

One of the most common pitfalls in developing CUJs is that organizations create too many of them. This was even true of Google earlier on, Barga-Avila said.

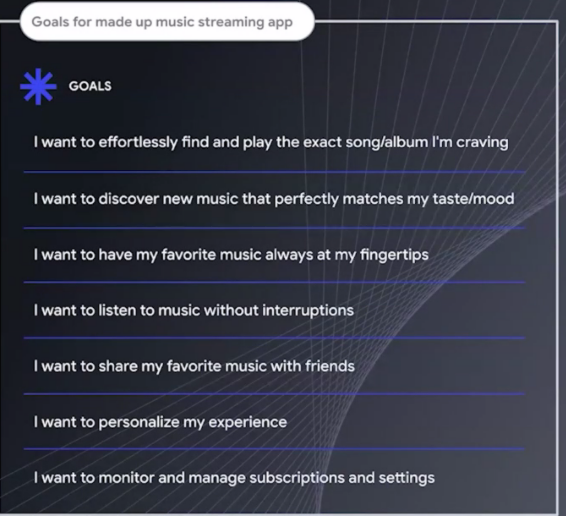

“In the beginning, we came up with spreadsheets of cojs that were completely not manageable and not helpful,” he said. “This is where you have to come back to goals. In most products, must users will have a couple of goals they want to achieve with their product.”

Five to seven CUJs is a reasonable number to work with, Barga-Avila suggested. These can be informed by pulling in customer support data and other existing research. He used the hypothetical example of a fictitious streaming music app, where the goals could include finding and sharing a specific song, music that reflects a user’s tastes or mood, as well as managing subscriptions and other offerings.

The task breakdown for the first goal might range from finding a song or playlist, opening the app’s sharing options and choosing one of them. However that task could take users in a number of different directions. Barga-Avila put up a flow chart that illustrated the way a user might take an action that leads to their desired end, but where they also might terminate, abandon or restart their tasks.

Success within CUJs can be measured at the goal level by offering up in-app surveys, he said, while log data and benchmarks could quantify how well tasks led to a happy outcome, according to Barga-Avila.

“When (the use of CUJs) started at Google, it was about defining those user journeys, maybe to test them in the lab and that kind of stuff, but it was not really about measuring them,” he admitted. “It was actually difficult for the CUJ effort to get traction within the company.”

Today, Google not only measures the impact of CUJs but takes action on them in a variety of ways. This includes weaving CUJs into product requirement documents and mockups, using them to structure user feedback mechanisms, prioritizing features, bug fixing and assessing launch readiness.

CUJs also need to be a shared responsibility, much like other aspects of CX design and management. While project managers might map CUJs to product roadmaps and plans, for instance, UX teams would focus on measuring the results, while senior executives might review CUJ scores at major events.

“Once you have success and you can show how you used the CUJs to improve, you need to celebrate that,” Barga-Avila added. “Call it out and show other teams how this can be used, so they’ll want to do the same.”

Barga-Avila’s complete keynote, as well as other sessions from Alida’s Innovation Day, are now freely available on-demand.

Shane Schick tells stories that help people innovate, and to manage the change innovation brings. He is the former Editor-in-Chief of Marketing magazine and has also been Vice-President, Content & Community (Editor-in-Chief), at IT World Canada, a technology columnist with the Globe and Mail and Yahoo Canada and is the founding editor of ITBusiness.ca. Shane has been recognized for journalistic excellence by the Canadian Advanced Technology Alliance and the Canadian Online Publishing Awards.